Chinese Whispers and Australian Wine – The Reckoning (Part 4/4)

Kaddy went insolvent.

Treasury Wine Estates (TWE) publicly said that even if China re-opens, it will be at least a five-year re-build.

Accolade has put Arras up for sale. When bankers sell the jewels, you know that they’re heading for the exits as fast as they can.

Treasury admitted that it can’t make money selling wine under $10 and is looking at axing brands possibly including Wolf Blass and 19 Crimes.

That was just one week’s news in the Australian wine industry.

Then, I saw this:

Even Yellow Tail is down 25% by volume in the USA since 2014 and GAINING market share there. That’s how bad the USA market is for other Australian wine brands through 2021.

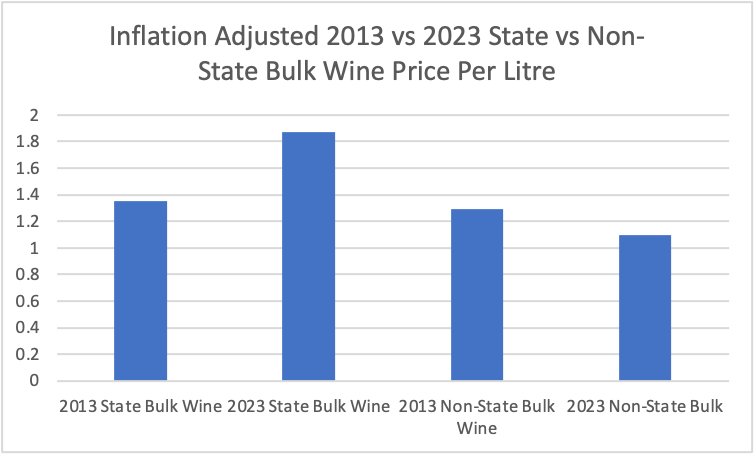

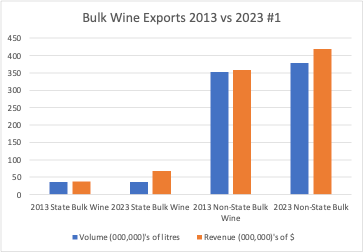

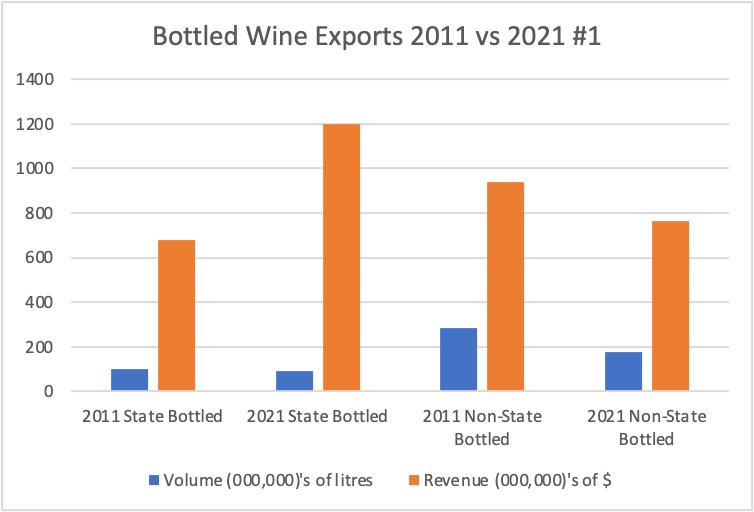

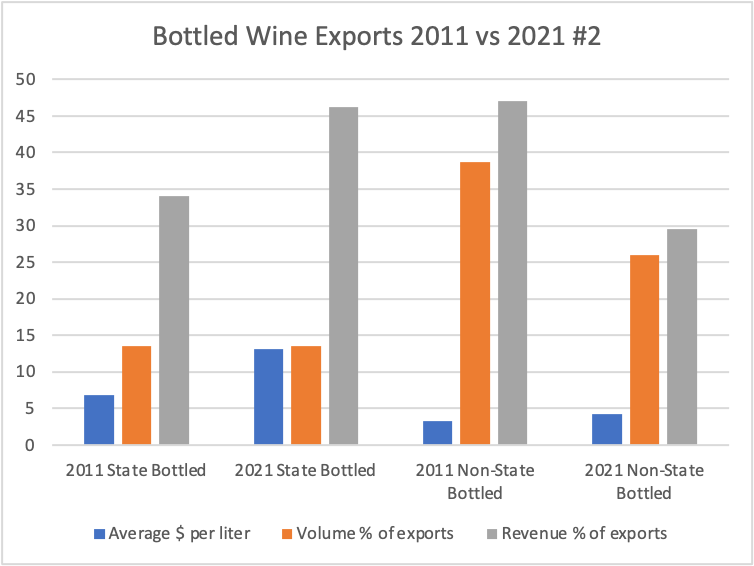

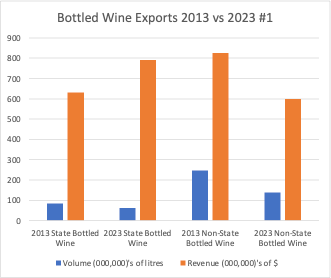

To get a better picture of how the China tariffs have and have not affected Australian Wine, if you look at 10-year inflation adjusted data from 2011-2021 to catch the pre-China tariff vibe and the 2013-2023 period to catch the post-China tariff vibe, a few major trends appear in both data sets. If you slice geographic indications data using state names vs non-state names (South East Australia, Australia, no claim made, Murray Darling) by prices paid per litre and then look at trends in bottled vs bulk wine, a pattern emerges:

What emerges is that Australian wine, whether bulk or bottled, fetches higher and increasing prices using at least a state name of origin or a region within that state. Wines that use “super” regional or no GI names have barely kept pace with inflation over the last ten years. As of 2023, nearly flat (non-state bottled) to a 15% decrease (non-state bulk) prices are the result. The good news / bad news here is that there is a visible path forward for the industry.

Digging more deeply, non-state bulk wine is getting bigger in volume despite non-state exporters not having any pricing power. This is the clearest result of overproduction – grapes with nowhere else to go

With bottled wine, non-state producers have been shrinking rapidly while staying just ahead of inflation with remaining products:

With bottled wine, there is a cross current of trends making it harder to understand at a high level but a bit easier at a lower level. First, non-state bottled wine has fallen rapidly in volume from a high base but appears to maintain pricing. State labelled wine has been flat-ish overall in volume with rapidly increasing prices to 2021 and then falling in volume as a direct result of China but still holding most of its pricing gains.

This last graph above is of special interest as the revenue as a % of exports is almost a mirror of state and non-state across the 10-year period with state clearly gaining at non-state’s expense by similar amounts.

It is a lot of graphs but they do help understand the situation better.

The graphs that brings it all home most clearly are these below measuring the percentage of change of all these variables from 2011-2021 and 2013-2023 assuming RBA rates of inflation:

This graph assumes 20.8% inflation to 2011 dollar amounts – source RBA 2010-2020 inflation calculator

This graph assumes 26% inflation to 2013 dollar amounts – source RBA 2012-2022 inflation calculator

Reviewing the two graphs above, it is clear that the negative gray bar in state bottled section in 2013 vs 2023 is overwhelmingly a result of the China tariffs while the non-state bottled sector was in pre-tariff decline in line with the other trends made clear previously.

These graphs illustrate that there is a tale of two cites here and possibly, two industries. One able to survive over time including the pressures of inflation while the other is losing to or barely able to keep pace with inflation while still growing rapidly as we saw earlier.

So where do we look for hope to sell all this wine?

Markets

For the bulk market, we can hope for bad harvests around the world or a slow bleed of inventories. Until then, domestic harvest capacity will be constrained until we clear these inventories. There are no quick solutions or markets where a huge amount of cheap wine is required absent some calamity somewhere.

For the rest of the industry, premiumisation focused on our best wine is the only path available. The big 5 customers (USA, China(!), UK, Hong Kong, Canada, Singapore) offer mixed opportunities.

China – someday, somehow it will be a growing market for us for higher priced offerings. But no bets being placed here for the reasons stated prior.

UK – a mature and stable market with a rapidly growing domestic wine industry and a bad post-Brexit hangover.

Canada has some upside but is a pretty mature market when viewed as a comparison market to the USA.

Hong Kong and Singapore both are popping higher in the data as large high value producers set up regional distribution there after leaving China. We still need to see what that means at the consumer level though as these sell through.

USA – of all the possible sources for significant and rapid potential growth, the USA alone can change things over the next 3-5 years. There is an enormous market for higher value wine that is simply not being pursued with the financial resources or expertise required. When you factor out Yellow tails footprint, we sell very little wine there compared to many similar but smaller markets.

Numerous other Asian markets all offer steady upside such as South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia though most have stiff taxes on alcohol limiting distribution to the top end of town. While we historically cheaper gear is sold to these markets in the past to compensate for the taxes charged, we need to learn the big lesson from China – the big end of town has a lot of money to spend on prestige products and little interest in lower priced offerings.

A New Way Forward

How do we accomplish this while working our way out from under our massive oversupply?

First we need to recognise the current crisis of over supply of grapes and wine as being the logical endpoint of our “biggest and best” wine producing country strategy of the last 30 years. While near and dear to its original proponents, it hasn’t and will not work in its current form. We need to choose from the two and focus on one. We have limited resources and we are not a large country. While we are drowning in wine that doesn’t make money (or earn sizeable foreign currency for the country) trying to become “big”, the choice for “best” is a lay down misere.

Despite recent slow to negative volume growth for higher end bottled wine from Australia, we need to be mindful that the poor reputation for Australian fine wine hasn’t been caused by this segment (at least since 2010) but the perception as being a low end wine country. Worse, we have not leveraged the opportunity these lower end offerings wines created for us by getting into the market. This double problem is not as hard to change or “fix” as it sounds over the next 3-5 years.

We all need to think about the whole system, not just the profits and sales of wine companies or our own particular niche. 25+ years of trickle down wine economics has been worse than it could have been for everyone, including the large companies and low value producers. We too soon forget approximately $5-7 billion in public and private market devaluations and write-offs lost in the 00’s, BRL / Hardy’s being flogged off (twice), the continuing financial bleed-out of farmers with off-farm incomes, etc. It has been a goat rodeo of historic proportions.

No matter how you look at it for Australian wine, pretty much every major market trend since 2017 points to the rest of the world wanting less cheap (particularly red) wine from Australia (and possibly everywhere else as well) despite ours being currently even cheaper than other countries’ bulk wine.

The roots of this continuing problem are systemic and deeply ingrained. For instance, volumetric grape levies go back to 1929 to when the wine market in Australia was entirely different than today with little price differentiation and no automation. Times change and new learning about old solutions has to be applied.

When things are tough, it is natural to feel that anyone making money in the wine game is “making all the money” and that all transactions are zero sum / “I win, you lose” affairs because, well, they usually are.

In a smarter system, oversupply and falling prices are not typical. Look at successful wine economies around the world for what they have in common – high(er) end offerings, robust wine tourism offerings built around strong regional identities with international consumption and investment.

Most importantly, almost all of these economies (Bordeaux and Rioja aside) do not suffer from an oversupply of commodity wine production. That Bordeaux recognises the problem and is already implementing the solution is instructive for us. In an environment of slight grape undersupply, everybody at all levels can make money and has an incentive to re-invest in improving the quality of their outputs.

Interestingly, many successful primarily bulk wine regions exist in countries that also have multiple regions that are world renowned. It seems that big can follow best, but best doesn’t follow big. The old “waterskiing behind a supertanker” idea turned out to not be quite right unless you like drowning.

For all these reasons, we need to seriously consider that almost every major existing policy since day dot has contributed in some way to our current undesirable situation. We have to learn and change, quickly. All policies and settings need to be examined in light of the incentives they create or destroy and how they interact with other policies.

One simple idea is to consider is adopting the “opposite George” tactics of George Costanza during his brief period of life success on Seinfeld as a template (not that there is anything wrong with it!).

Another is to consider that perhaps we don’t know best for all these reasons including our inability to divorce ourselves from deep self-interest and that we enlist help from serious global policy wonks to do the analysis for us.

The ideas and suggestions put forth below are a non-comprehensive list of policies, settings, conversations and points of view we need to consider to re-start the Australian wine industry on a path of growth and excellence. My goal in provoking this dialogue is dramatically growing the size of the Australian wine pie profitably over time. To make this happen, we first need to insist on as much involvement by folks in positions of responsibility (vineyard and winery owners, etc) and not leave it to those interests that have failed the greater “us” over recent decades.

To those who don’t know, my views are mine alone and have been developed over twenty years of bewildered curiosity and engagement in Australia as a grower, winemaker, regional association Chair, CEO and Chair of an industry supplier, writer and industry critic. All of those roles imposed different demands about how to think about problems facing the industry and afford me a perspective different to most. And, I’m totally independent of any other interests.

There are no easy wins available for us in any market or any direction. If we do not insist on better systems, we can’t expect better outcomes. Having said that, there is no good reason that this can’t be a staggeringly successful industry if we are to consider it with fresh eyes and adapt to the world as it is now rather than the one we were bequeathed by those who were successful in another time.

Australian Grape and Wine

The monopoly power of the AGW to speak to Wine Australia and the federal government on behalf the entire wine industry needs to be reformed before other large changes can occur. The AGW membership needs to change the archaic rules of AGW governance under its existing rules including:

The Board of AGW must be elected by its members with an independent auditor of results as with any well governed association or corporation instead of the exclusionary system of hand chosen and appointed Board members.

The threshold for all decision making on the Board must be 51%, not 80%.

Ideally, their membership structure should be opened up so that it can effectively represent the entire industry, not just the 10-15 winemaking companies that dominate it and the rump of grower representatives with no power. As it stands, given that there are four colleges of three Board members each (small, medium, large, growers), any one sector or any three individual Board members can prevent any and all changes.

There must also be a public declaration of interests and possible conflicts of interest by all Board members such as purchase or sale agreements or events, other Board seats held, shared ownership or participation agreements, etc. prior to nominating for election. Individuals who do not wish to have their interests scrutinized by their peers shouldn’t run for industry Board seats.

All of the above are common sense / assumed governance principles and should be embraced as such immediately if only to not be seen as the source of the problems that the AGW is entrusted to address.

If they choose not make these basic changes, it is clear that their Board does not embrace the requisite duty of care for the industry and members should either leave, force its wind-up or ask the government to step in. They have had decades to address these problems with little to show for it.

Levy Reform

Serious and substantial levy and policy reform must occur to fund Wine Australia appropriately over the long term in a way that reflects the needs of the ultimate payers, growers and taxpayers. The most obvious reforms appear to be to implement an ad valorem rate / % of value system where the value of wine grapes or wine sold or purchased determines the amount levied rather than the current volumetric system. The current system is also viciously biased to favour large levy payers over small levy payers. The levy system must be common to all regardless of size for many reasons including fairness, broad buy-in and, possibly, lower overall rates for most.

Grower Profitability

The focus needs to be on profitable long-term incomes for growers regardless of segment by reducing oversupply. This will only occur in the short to medium term as a result of substantial and long-term / permanent vine removals. How these are determined should be somewhat evident but studied by serious people who are not conflicted by their roles (or their clients) in the wine industry. We don’t need Big Four type consultants, or various in-crowd industry consultants or accountants like those used in Vision 2020, we need serious economists and policy wonks from across the world who have studied these matters for decades.

Thinking a bit, this is the sort of role where Kym Anderson should act as an independent chair where he appoints the committee to make recommendations, not industry or government. Kym’s domain knowledge of the wine industry and policy is unrivalled and his work is respected worldwide.

Business and governments will have to be part of the process to be engaged in the changes required but they shouldn’t be voting members. Both have had 20 years to address the status quo and fluffed it. Time to let serious policy thinkers who deeply understand the industry have a go.

One suggestion is to set up a cap on vineyard area(s) with a permit system overseen by Wine Australia to prevent over development / oversupply in undesirable sectors or regions the future. It should in no way be used as a system to seek rents but adjust as market pressures and trends adjust. For example, growth would only be permitted once regional prices have reached sustainable levels for growers and producers or, perhaps, to plant new varieties to keep the industry moving forward.

Health Lobby

Make a long-term “big picture” deal with the health lobby and government now and end the health lobby’s long-term assault on the wine industry – at least in Australia.

a) Taxation of alcohol must be considered on a volumetric basis rather than the current ad valorem basis perhaps phased in over five years. With volumetric tax likely to reduce overall harms caused by the excessive consumption of wine, perhaps the total revenue “cut” for government could be revised downward as well.

The current approach of an “un-bonded / non-excise” taxation approach should be maintained. That was one thing we got completely right.

b) Tighten alcohol labelling to +/- .5% from +/-1.5%.

c) A “once and for all” domestic health warning on wine packaging should be agreed to, not subject to review for at least a decade.

d) Recognition that the wine industry is “different” to other alcohol industries with different regulation and tax rates warranted for many reasons.

Solve Multiple Problems to Engage Government(s)

The biggest domestic policy issues in Australia over the next fixe years (at least) are climate change and housing affordability. Uprooted vineyards, particularly on the Murray Darling River system, are ideal places for retirement communities and large scale solar farms equidistant to three state capitals representing about 3/4’s of the nation’s population.

Planning for housing should be close to existing towns / infrastructure and large scale solar sites close to existing transmission corridors. Affordable retirement (and other) communities require cheap land, tradies and investment to build them and lots of good paying support jobs (particularly healthcare) on a long term basis.

With 10 megalitre per hectare permanent vineyard water licenses, about 50 new households per hectare could be guaranteed water without increasing river drawdown. Nearby solar can power all the AC needed quickly in warm summers without increasing carbon production. Perhaps they could be a locally owned resource driving down power bills for all those in that region.

With increased population, existing sewage systems can be upgraded to provide second use water for the beautification of common areas for the community. Mildura’s population could double with cashed up retirees in less than 10 years on just 400 hectares with healthcare access for all vastly improved. If this sounds fanciful, Phoenix wasn’t much of anything except sunshine, oranges trees, cheap electricity and Colorado River water seventy years ago. Sound familiar?

Wine Australia and Promotion

Establish a realistic and aggressive long-term requirement for overseas wine promotion and fund it appropriately based on the value of grapes or wine sold. High value grapes and wine have far greater margins to support promotion and employment than cheap or bulk wine. Moreover, to increase future revenue, Wine Australia’s interests would be aligned with growers and wineries through increasing prices and income, not increasing tonnage.

Instead of marketing “Australian Wine”, we need to market high value Australian wine regions and wine growing locations. The “they don’t even know where Australia is” marketing argument about overseas consumers of the last 20+ years is dumb and shouldn’t be entertained any longer.

People who spend more money on things are people who want some brand assurance for their purchase even if they don’t know much about it. In fine wine, that assurance starts with regional names. Having said that, how many Champagne drinkers can stick their finger on a map and say “there” in finding it? Not many. This is how to counter this seriously dumb argument the next time you hear it.

Lots of wealthy consumers all over the world have only the vaguest ideas about where Champagne, Bordeaux, Napa, Sonoma, Tuscany, Piedmont, Barolo, Burgundy, Sonoma, Marlborough and Rioja are located but they happily buy wine from these places for many multiples the price paid for those from our best regions let alone “South East Australia” and “Murray Darling” (incidentally, these are not not even actual place names someone could find on a map!). (Grange, HOG and a few others aside obvs., don’t at me…)

Wine Australia’s present branding is “Australian wine Made Our Way”. This focuses on two ideas 1) Australia and 2) how we make wine. While I get the idea that is trying to be communicated (our larrikin spirit, etc), what if people like (or, worse, don’t care) the way other countries make wine they already like? How many Champagne consumers know what or how many varieties of grapes (seven, two red and five white) are allowed in Champagne? Or that they spray copper on their vines 20 times a season on average? BUT, they know they like Champagne and not that other stuff. And, they have money.

The question that we need to answer is, “why would or should a new consumer consider Australian wine assuming they already like wine from other places?” Wine Australia chose the process of winemaking (Made Our Way) for a point of marketing differentiation because it suits big multi-region wine blenders including TWE / Penfolds, Pernod / Jacobs Creek, Casella / Yellow Tail, AVL / most, Accolade / Hardy’s) that are not encumbered by old world winemaking rules. Fair enough. But, aside from the commonality of “Made Our Way”, the only things these companies have in common are wine and Australia.

While this makes “Australia wine Made Our Way” the perfect slogan to market to big Australian wine companies. How many consumers know or care about our stated point of difference compared to Methode Champenois, the blending rules of Bordeaux, the Cru system of Burgundy? We are looking in, not out.

Meanwhile, spending our promotion money on the generic term “Australia” is associated most strongly in wine terms in North America with “Yellow Tail” where it now has 50%+ market share. (Should this be considered a success of Wine Australia marketing then?)

The consumer knows Australians make wine but Wine Australia appears to think too little of them to go beyond “Australia” to “Explore Australia through Wine” for instance. Or maybe it hopes millions of consumers will stop their busy lives to say “well, tell me how you make wine then.”

I have long championed the step ladder theory that says consumers liking Yellow Tail will trade up over time to other Australian wine. YT definitely got folks on the first rung but we haven’t told them about the amazing things they will discover further up the ladder well. And, as the numbers suggest, the folks on rung number one have been wandering off the past 5-10 years. We urgently need to tell them about the rest of the ladder of great wine regions and wine experiences and to help them explore on-line, in-person and, most importantly, on and off premise to build our our offering. For instance, what is Wine Australia’s strategy to use TikTok? I get at least three TikTok’s a day sent to me about things far more mundane. But I watch.

All of these suggestions line up with the data that “wine from nowhere” brands like Yellow Tail (sorry to pick on YT, they have done extraordinary job at a tough price point) are also part of the fastest shrinking export segment of our industry (South Eastern Australia / non-state bottled). These brands have the least ability to increase margins faster than inflation while paying the least in marginal levies to support overseas marketing and paying the least for grapes. The irony never stops once you start looking. Meanwhile, growers from the main areas of inland grape supply are dominating the conversation in industry governance circles by complaining about R&D investment and levies.

The entire system is literally and spectacularly all backwards.

Wine Australia should back the regions willing to back themselves with promotional funding. If they won’t back themselves, that is their choice. Insist that levies in all regions be fair / equal for all levy payers on an ad valorem basis. We are in this together or we are not.

Australia needs world renowned “hero” regions. If you think Barossa Valley, McLaren Vale, Mornington, Yarra, Margaret River, Hunter, Tassie, Clare etc are “internationally renowned” hero regions in the same way as the regions mentioned above, you may not know a lot folks with money to spend on wine in other countries. Or, to see a peer type hero region, visit Stellenbosch. Having visited twice, I assure you that we have nothing close to what they offer overall and they are on the same time zone as most of Europe.

In fairness, Wine Australia can’t (visibly) pick winners from its individual levy payers, but it can recognise regions. Large Australian multi-region wine companies would be wise to invest in more than one cellar door in just one region and embrace regionality even if they do not do so on their labels.

While a certain large brand may have been most important to the growth and identity of a region, such as Hardy’s in McLaren Vale, it is regions that will lift and support big brands in a sustainable pyramid over time as customer preferences change. How many people visit McLaren Vale because of Hardy’s today compared to thirty years ago? Times change. Economies change. Marketing and promotion needs to change with it. The relative brand power between regions and wine brands has changed dramatically over the last thirty years. Vineyard prices alone are a more than adequate proxy for this assertion.

Another way to look at this seeming chicken and egg question is that power of the brand Silicon Valley has never been higher despite almost no one knowing about Fairchild Semiconductor or HP’s oscilloscopes.

Cheap and bulk wine doesn’t need promotional funding – it is a commodity. It needs low costs like low and stable electricity prices from nearby large scale solar and battery. If a region wants promotional funding, they should have to make high value added wine from “somewhere” and be willing to support it with a regional levy.

Conversely, Ricca Terra and a few others in the Riverland are showing how to escape the poverty trap of growing bulk or low value winegrapes and brands in these regions. Those are the businesses / brands that should be supported with levies there.

We need to ditch the confusing South East Australia and Murray Darling designations. These super regions can simply use “Table wine of Australia” or similar on their products. Consumers across the world will understand this just as they understand “Vin de Table”, “Vino da Tavola” and “Vino de Mesa”. What they can’t understand is places that don’t exist on a map.

High value wine has more employees, more marketing people, design people, sales people and vineyard workers per input while using far less irrigation water. What outcomes have we designed our systems for? How can we have maintained such perverse incentives for so long? Or, more importantly, for how much longer?

Research and Education

Serious thought needs to be put into the educational and research bodies roles and staffing. The AWRI needs to be appropriately funded by levies and matching taxpayer funds so it can do important research without spending its limited energies chasing additional revenue or appeasing noisy levy payers.

Further, there needs to be a “Chinese wall” (ironic, heh?) between research and industry politics. This will also reduce the possibility of the appearance of conflict of interest between employees with grape and wine interests and wine companies. This should apply at Wine Australia as well.

AWRI employees shouldn’t be paid to be embedded in Boards of regions and industry bodies etc. They should be creating valuable research directed by research priorities agreed with Wine Australia. The AWRI shouldn’t be the hotbed of industry intrigue staffed with corporate and business development managers, industry liaisons, etc. It needs great researchers focused on meaningful research of benefit to levy and tax payers of Australia.

The political shenanigans at the AWRI do nothing to foster a culture of greatness across the industry. And, as AWRI chases marginal revenue like grants at least some of the great talents employed at AWRI are being squandered to attract and deliver on revenue which isn’t necessarily even from or for the wine industry! These talents will find new places to do work they care about if this doesn’t change in my opinion. Screwed up management conditions like these are exactly what we used to look for in my 16 years of experience recruiting world class technical talent for great companies.

Also, the Universities (Adelaide and Charles Sturt in particular) need appropriate long term Wine Australia funding; last I checked on the University of Adelaide – one of the worlds’ great oenology teaching institutions – didn’t have an oenologist on staff. They had reportedly left for a position in the growing UK wine industry or academia. What a disgrace.

Short-term Research Priorities

Investing large sums in research to make low value grape growers slightly more efficient is the wrong answer for the entire industry. There is no good money to be made from $400 grapes without someone losing out badly. Lack of investment in research on behalf of any sector is not the cause of our major problems. Manufacturers and suppliers do this sort of work worldwide as a matter of their existence – we don’t need to do it for them, at least until we have our own house in order.

Wine Australia Governance

This one is a conundrum. Only an independent body with deep skills can be entrusted with long term planning for research and promotion. And, only governments can be entrusted with regulatory affairs. But imagining a government department creating and executing world class marketing over a long period of time is a real leap of faith.

Wine Australia doesn’t have one great luxury / super premium marketer on its Board or team. We need insights from brand driven consumer luxury industries – music, fashion, art, hospitality, autos, etc. To get those, you need numerous people who have lived in those environments on an operating and governance basis and know what serious brand building means without being overseen by board members who lack this domain knowledge. If we want to win, we need to start at the top.

While a couple of capable and successful winemakers are a “nice to have” on the Board, were the most strategic and insightful candidates recruited for these positions as happens at the best governed companies?

At the operating level, we have an academic in the late part of their career running the show, not someone with a demonstrable need to prove something on the world stage. Given the gravity of the industry’s troubles this isn’t exactly The Dream Team we need.

The structure and remit of the Board needs much greater focus on the only objective we can afford – making and selling triple bottom line sustainably great wine worldwide. Research, sustainability and the lot need to be aligned behind that spear tip. That the execution of this strategy may not be solely executed by government employees must also be considered.

Only the Federal Minister for Agriculture Murray Watt can make the initial decisions necessary to start this process however. Share your thoughts with him at: minister.watt@agriculture.gov.au

Resources – growing 16 tonnes of grapes worth $6400 per hectare to make 11,000 litres of wine worth just $11,000 (or less) on one hectare while employing 10 million litres of river water for irrigation to grow the grapes isn’t a great deal for an inland grower, their community or the environment of Australia.

By contrast, the same 10 million litres used in McLaren Vale (the area I am most familiar with) could produce at least 45 tonnes of wine grapes worth $76,500 at current average prices from 9 hectares producing 30,000 litres of wine worth at least $120,000 in the premium bulk market or multiples of that as bottled wine at wholesale.

Sadly, neither example is sustainable for either grower because even the grower in McLaren Vale needs at least $17,000 per hectare to turn a profit of any sort because the price of land is at least three times that of the former example and a 9x multiple of land use is required to grow this quantity of grapes.

This is a simple illustration as to how oversupply affects the value of the entire country of wine grape growing, not just the bottom of the market. China only accelerated to our problems that were homegrown over the twenty+ years prior.

Assuming that some drastic vineyard area reduction occurs, we need to make sure those left behind are treated with respect and have options, some of which are suggested above. This will be a key metric that those who remain will be measured by.

Finally, there is one other possibility – two industries – one for high value and another for low value – that require two industry associations and all the chaos of policy and execution that would entail for all involved. Maybe the other suggestions made above seem more sensible in that light and will be acted upon.

And, maybe someone in a position of authority might ask Kym Anderson if he has some ideas how he might be able to help out.

Except as otherwise noted, all data sourced from Wine Australia website. It is an excellent resource freely available to all.

End 4/4

Postscript:

Meanwhile from todays Vino Joy News: “Alarm bells are ringing for sky-high Bourgogne prices but it’s unlikely there will be price adjustments in the short term, says BIVB president, citing blistering market demand and low stock as main reasons.”